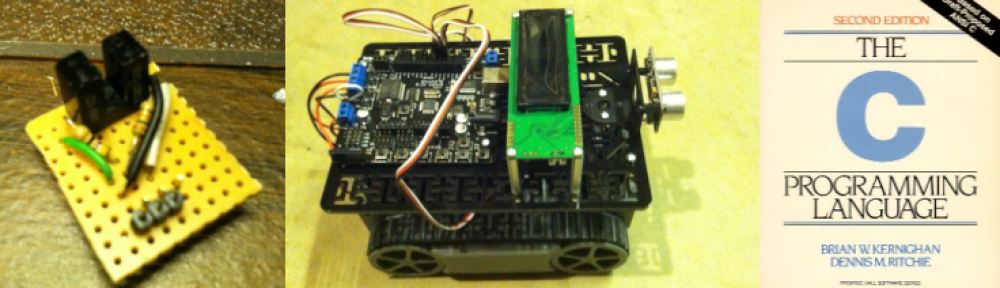

I’ve posted previously about Udacity’s Programming a Robotic Vehicle course. I think that online courses may come to revolutionize college experience. However I recently read a thorough and well-written critique that reaches the opposite conclusion, and thought it worth revisiting.

Since taking that course, I’ve also started taking Udacity’s statistics course, mostly as a refresher, and I’m about 2/3rds of the way through. Thus, I read with interest AngryMath’s critique. AngryMath is a college level statistics instructor in New York City. He has a very harsh critique of the course, and by extension, the whole MOOC model. He highlights 10 major problems and I think he makes a lot of good points, but that he over-generalizes in his criticism. You can read his full critique on his site, here I list some of them and offer my thoughts:

- Lack of Planning: I agree. The original syllabus seems to have been published in advance of the course, it’s not particularly well-organized, and doesn’t introduce material in the best order. It seems much poorer in this respect than the robotic vehicles class. However, that’s an indictment of this particular course, and this can occur in online and conventional courses.

- Sloppy Writing: Again, I agree. AngryMath also cites the lack of a textbook or written material. I don’t think a textbook is needed, but course notes similar to those developed for the robotics course would be helpful. I certainly found them helpful in that course. AngryMath has only sampled the statistics course, so has not reviewed this approach.

- Quizes: He thinks they aren’t in the best places and criticizes when they are used to introduce material. I DON”T agree that they come in out of the blue to introduce material, and I like that approach occasionally anyway. Try things out on your own first.

- Population and Sample not properly distinguished: Again, AGREE! I’m taking this as a refresher, so knew a distinction was being overlooked and researched it again on my own. More generally, this is a criticism I have of both Udacity courses I’ve taken. It’s fine to simplify and present a high level sample, but let the student know you’re doing it and where to get more information.

- Final Exam Certification: AngryMath criticizes the certificates as meaningless, because you can repeatedly answer the same static questions until you get it right. This makes the “certificate of accomplishment” meaningless. Well, yes, at the present time, for this course, BUT 1) they’re already working to set up standardized, monitored testing using existing testing companies to offer “real” certification. If you’ve ever taken a test at one of these facilities, it’s more heavily monitored than a typical college final. Udacity makes no claims about the value of their current certificate, and are working to add this feature; 2) While a few multiple choice questions can be taken again and again until you get it right without true understanding, it’s easy to add variation to the questions, even if that wasn’t done in this course, and for courses with programming assignments, random guessing won’t work; and finally 3) The retake until you get it right approach can be a good learning model if you eliminate the other issues and make the questions different.It indicates what you’ve learned by the end, rather than how much you picked up the first time.

So, while I’m learning from the class, and intend to complete it, I agree with AngryMath that the course is done rather poorly, has errors, and could be much better. Where I disagree is his generalization:

“Some of these shortcomings may be overcome by a more dedicated teacher. But others seem endemic to the massive-online project as a whole, and I suspect that the industry as a whole will turn out to be an over-inflating bubble that bursts at some point, much like other internet sensations of the recent past.”

I believe MANY of the problems in this class are specific to the class, especially having taken the much better Programming a Robotic Car class. While the online model has many shortcomings compared to live teaching, unlike AngryMan I believe many can be adequately worked around. For example, I found far more information in the crowd-sourced robotic vehicle course forum and wiki than I can recall getting from office hours and recitation sections in a live class. Other shortcomings will clearly remain. BUT, and this is where I part company totally, I don’t believe the shortcomings exceed the savings. If I can get 80% as good a class at a 10th or less than the current, and rapidly rising, cost of a traditional college course, then this is clearly the future. Perhaps not entirely, and I hope not, as the college experience is often one to be treasured. But I can easily see the competition of MOOC’s forcing a new model, perhaps just one or two years on campus, and the rest done with far cheaper MOOCs.

Also, online courses offer a chance to “teach the long tail.” Small colleges can’t have the breadth of faculty to cover all topics at advanced undergraduate or graduate levels. In addition, maybe only 1 or 2 students at the college is interested in the topic. Many times, college and universities in physical proximity will offer the opportunity to get credit for attending classes taught at nearby schools (e.g., the Five College Consortium in western Massachusetts). Imagine “virtual consortia” of hundreds of schools throughout the country (or even the world). Through this model, the 1-2 students per college can be virtually assembled to form a sizable class, taught by a well-qualified professor from one of the consortium’s schools.

Bottom line: AngryMath has a strong, valid critique of Udacity’s Statistics 101 course, but it’s dangerous both to infer the quality of other current classes from a sample set of one, and equally dangerous to extrapolate to the future.

For yet another take, there’s a good article in Forbes: Massive Open Online Courses — A Threat Or Opportunity To Universities?